ITCHS Home

December Comedy:

Studies in Senior Comedy and Other Essays

Just what is the role of humor in negotiation?

The Legislative Simulation asks participants to negotiate a hypothetical budget under severe fiscal constraints and then to indicate which negotiation techniques were used by which members of their negotiating group.

Humor was built into the structure of the test, particularly in the public embarrassments which plague each of the five departments.

Each participant’s budget is compared to other budgets of the same portfolio—Highways to Highways, Colleges to Colleges— and expressed as a percentage of the average budget awarded to that portfolio. That percentage score is then compared to the other percentage scores for the same G-5 to determine rank within the G-5.

Overall women were more represented than men, and they ranked on average higher than men.

Men tended to receive more nominations for individual negotiating tactics.

The results indicated that for both men and women, use of proactive humor is associated with different negotiation results than is the use of reactive humor.

Thus for men, being perceived as joking was associated with success, while for women being perceived as not joking was associated with success.

For women, the use of reactive humor is especially associated with Rank III.

Humor negotiating techniques were all used as part of a larger strategy or stance.

It is notable that the male success profile includes both reactive and proactive humor, while the female includes neither

For women, reactive humor can be valuable for a safety play, but proactive humor is highly risky.

Chapter 7

Surviving Negotiation with Humor

Part I: Gender Differences

by Robin and Paul Grawe

Presented at the Conference of the International Society of Humor Studies

Edmond, Oklahoma, 1997

Edited for web publication

Advice on how to successfully negotiate is not hard to find. Aristotle gave it. And so do the self-help sections of nearly every book store. Such advice, however, rarely includes using humor. The advice may be given humorously. (See Herb Cohen’s You Can Negotiate Anything. New York: Bantam, 1982.) But it is not likely to discuss how humor can be successfully employed as part of negotiation strategy.

Yet one need spend only a day or so at a state capitol—where negotiation is what it’s all about—to recognize that legislators laugh a lot—probably more than bureaucrats. And the laughter increases as the close of the session approaches. The fact that laughter is associated with very serious negotiation though omitted from discussions of negotiation strategy led us to ask the question, “Just what is the role of humor in negotiation?”

To discover what negotiating techniques are operative in a group negotiation setting and how humor fits into that mix, we designed the Legislative Simulation (LS) which asks participants to negotiate a hypothetical budget under severe fiscal constraints and then to indicate which negotiation techniques were used by which members of their negotiating group. The designation allows us to determine not only which strategies are most effective over all, but also which strategies are most effective for certain types of people – men or women, for example, or left- or right- brained people.

The LS was first administered at Augsburg College, Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1990 for a graduate practicum in Augsburg’s Masters in Leadership program. It was subsequently given in upper-division classes at Winona State University, to Japanese students at Winona State, and to Japanese students at the MNSCU campus in Akita, Japan. Initial results regarding left- and right-brained uses of humor for American participants were sent to the 1992 International Conference on Humor Studies in Paris. Additional participants since then have allowed us to consider gender differences in the use of humor in negotiation.

1

Instrument Design

The LS divides participants into groups of five (G-5’s) and asks each G-5 to negotiate a budget for the mythical State of Minnehaha, an upper Midwestern state bordered by Nakomis, Michemakwa, and Upper and Lower New Germany, as seen in the map below:

Map of Minnehaha and Neighboring States

Each participant acts as a voting legislator as well as a lobbyist for one of the five portfolios: K-12 Education, Colleges and Universities, Highways, Natural Resources, and Welfare. Participants are all given a basic fact sheet regarding the budgetary woes of Minnehaha, including budgetary requests of all five portfolios (which total 1,440,000 units), the previous year’s budget (which totaled 1,100,000 units), and the Governor’s proposed budget (of 1,000,000 units). Participants are also given an additional fact sheet of Recent News Items relating to all of the portfolios, and a fact sheet specific to their portfolios. These fact sheets provide the raw materials for persuasive argument.

2

It should be noted that humor was built into the structure of the LS, particularly in the public embarrassments which plague each of the five departments. For example, the state university plays in the “Big Dozen Conference”; river advocates are sporting bumper stickers that say, “We can’t all live up the Gumie”; a metropolitan newspaper carries a photo of a DNR agent holding a 15 pound walleye in someone’s face; and when a high school teacher arranges for her lover/student to do away with her husband, the legislature is abuzz. Built-in humor makes what might be a somewhat tense exercise a little more fun and further simulates the legislative atmosphere.

Testing Procedure

After time to study their fact sheets, participants are asked to make a short presentation—pitch, if you will—for their portfolios. Then, usually after a short break, the G-5’s negotiate their budgets. Budgets must total no more than 1,000,000 units, down from the initial requests of 1,440,000 units. Any G-5’s which do not arrive at a final budget in the allotted time are granted the Governor’s budget.

After negotiation is completed, each participant is asked to indicate which two of the five participants in his or her G-5 was most noted for each of 22 potential negotiation techniques. The list includes such traditional tactics as morality, precedent, persistence, and reward or punishment. It also asks, “Who told the most jokes?” “Who laughed the best?” Who took kidding and jokes the best?” and “Who was the best humored?”

After negotiated budgets are collected, each participant’s budget is compared to other budgets of the same portfolio—Highways to Highways, Colleges to Colleges—and each budget allocation is expressed as a percentage of the average budget awarded to that portfolio. That percentage score is then compared to the other percentage scores for the same G-5 to determine rank within the G-5. Thus the member of each G-5 who receives the highest percentage score was ranked I, the member with the second highest percentage score ranked II, and so forth to rank V. Thus even though different portfolio budgets vary greatly, we can determine “winners” within a G-5 based on a comparison of portfolio budgets.

More importantly, because participants nominated fellow negotiators (or themselves) for frequent use of various negotiation techniques, we can ask which negotiation techniques are perceived by fellow negotiators to be associated with various ranks of success. And from other information given by participants about themselves we can ask which negotiation techniques are associated with which rank among various subgroups, such as males or females, those under or over 40, left- or right-brained participants.

3

Gender Differences

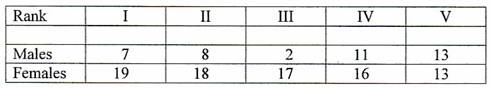

Before considering the particular tactics associated with male and female negotiators falling in various ranks, it is useful to look at the overall distribution of male and female participants across the ranks of negotiation success, as displayed in Figure 1.

Distribution of Participants by Rank and Sex

Figure 1

Overall women were more represented than men, and they ranked on average higher than men. (It should be noted that when the total number of participants in a negotiation was not a multiple of 5, some groups were reduced to 4, eliminating for those groups a Rank III. It turned out that only 2 men fell into Rank III, which makes male Rank III results virtually meaningless.)

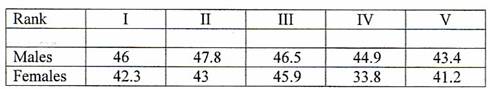

While women tended to rank higher than men—that is, were more successful negotiators—men tended to receive more nominations for individual negotiating tactics. Figure 2 shows the average number of nominations for all negotiating tactics received by male and female negotiators in each rank.

Average Total Nominations

Figure 2

4

The averages indicate a slight tendency for men in Ranks I through III to receive more nominations than those in Ranks IV and V; that is, the more successful men were generally more noted—noted for anything—and perhaps more noticeable than the less successful men. More remarkable, however, is the nomination pattern for women: there is a marked drop in the nominations given to women in Rank IV. That is, there is a tendency for women who were small losers (Rank V being the lowest) to be not noted for anything (p<.002). We have labeled this phenomenon the Wallflower Effect because it appears that for women a small loss is associated with fading into the woodwork.

Proactive vs. Reactive Humor

The list of possible negotiating techniques for which participants could be noted included four humor factors: joking, taking kidding, laughing, and being good humored. In order to better understand the function of humor in negotiation and how this function differs between men and women, we distinguished between joking which is proactive, initiative humor and the other three factors which are reactive, responsive humor. (For a fuller discussion of proactive and reactive humor, see Paul Grawe, “Reactive Humor and Negotiating Success,” International Conference on Humor Studies, Paris, France, 1992.) The results indicated that for both men and women, use of proactive humor is associated with different negotiation results than is the use of reactive humor.

Male participants in all five ranks were more noted for joking (average noted = 2.15) than were women (average noted = 1.28). This difference is well above the 99% confidence level. And in fact, several participants in all-female G-5’s have insisted that none of their G-5 participants joked at all. The fact that men were perceived as joking more than women is consistent with considerable gender-communications research as well as with the “old boy” sensibility. (Don Nilson in his inimitable thoroughness has provided us with an extensive bibliography of publications on gender difference in humor, some of which discuss gender differences in joking. None, however, look at how these differences function in negotiation.)

5

Humor and Negotiation Success

The important question here is not how much participants joked, but did it do them any good? In fact, for men, joking was positively correlated with negotiation success, the men in Ranks I, II, and III being more noted for joking than those in Ranks IV and V (p<.058). For women, however, joking was associated with loss, the women in Rank V being more noted for joking than those in Ranks I through IV (p<.028). Thus for men, being perceived as joking was associated with success, while for women being perceived as not joking was associated with success. The graph in Figure 3 shows the pattern of recognition for joking through the success ranks for men and women:

Figure 3

This graph suggests that perhaps it is wise for women to engage in less proactive humor than men if their goal is negotiation success.

A different picture, however, emerges for the use of reactive humor: laughing, taking kidding, and being good humored. For all ranks, men were only slightly more noted for use of these three techniques combined (average=5.78) than were women (average=5.09), not a significant difference. However, the distribution of reactive humor nominations over the five ranks is noteworthy: For women, the use of reactive humor is especially associated with Rank III, a middlish result, neither a big win nor a big loss (p<.031). Thus for women, reactive humor may be associated with “safety play.” Such a technique may not pay big dividends in any one negotiation but over time can be a very valuable tool. In situations where great gain seems unlikely and loss looms, or where the situation itself is high risk, a middle board may be a welcome outcome and a safety play the wisest strategy. The graph in Figure 4 shows the recognition for Reactive Humor through the success ranks for men and women.

6

Figure 4

Humor as part of a larger strategy

It should be noted that while we have isolated humor techniques for purposes of analysis, in reality they as well as other negotiation tactics were all used as part of a larger strategy or stance. For findings relating to proactive and reactive humor to be maximally useful, we need to see them within the larger panoply of negotiation tactics. If we identify those negotiating techniques frequently noted for Ranks I and II participants and infrequently noted for Ranks IV and V, we can create these success profiles for men and women:

Success Profile for Men Success Profile for Women

Being good humored Persistence

Persistence Uncompromisingness

Authority Authority

Joking Morality

Outspokenness Reward or punishment

Originality Helping pass the budget

7

It is notable that the male success profile includes both reactive and proactive humor, while the female includes neither. Both formulas included such traditional techniques as Authority and Persistence, but men temper these with humor while women use only helping to pass the budget.

If we similarly devise anti-success profiles from tactics frequently associated with Ranks IV and V and infrequently with Ranks I and II, we can create the following profiles:

Anti-success Profile for Men Anti-Success Profile for Women

Concession Concession

Kindness Understanding

Understanding Friendliness

Seriousness Risk-taking

Precedent Joking

It is notable that for women, proactive humor is associated with a losing strategy, while the male loss pattern lacks humor of any sort and is marked by “seriousness.” It would seem that for men, humor, both proactive and reactive, is essential for negotiation survival. For women, reactive humor can be valuable for a safety play, but proactive humor is highly risky.

8

Next Chapter DC Contents DC Cover ITCHS Home