Comedic Tenor, Comic Vehicle:

Humor in American Film Comedy

Disney has been routinely academically ignored and minimized.

The Disney classics are the “Great Books” that unite young American culture.

Particularly its animated films have had a shared common mission, to influence the meaning of the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights.

High literary talent expects to get paid. Academic criticism that can’t work with that expectation can’t work with reality.

Student censure of Disney routinely falls away shortly after college as former Disney fans return to their original loyalties in buying classics.

The Disney organization plans its classics in advance.

All its productions unite the talents of artists working in very distinct arts.

We are tossed in medias res into a typical morning in the street-rat life of Aladdin.

Each component of the comedic A Theme can be reasonably argued as part of a long-term Disney interpretation of American values.

Jasmine chaffs under a thoroughly un-American demand that she marry for state convenience.

A musical dialog contrasts views of palace life, Aladdin seeing the palace as a pipe dream, and Jasmine seeing it as a nightmare.

The B Theme begins with the entrance of Genie.

Theme B replaces the repeated Gotchas of Theme A with an elaborate and extended Word Play extravaganza.

Theme B also portrays Aladdin, by his own wish, choosing to become something that he is not.

Aladdin flies back to Agrabah in the faith that Aladdin the Street Rat honestly lived is considerably upscale from Prince Ali Ababwa dishonestly endured.

Ultimately, they win by their resort to improvisational psychology.

The grand Gotcha on Jafar leads into a coda ending, the freeing of Genie and his improbably long exit reprise of the verbal virtuosity of the B Theme.

Aladdin returns to hero status by adding to the A Theme success formula of self-reliance, generosity, quick-wittedness, and improvisation the B Theme success traits of genuineness and honesty.

The Disney social agenda has been designed not just for America but for the world at large.

The humor texture of Aladdin shifts, at least strongly in emphasis, along with the A-B-A musical structure.

The opening scene in Agrabah features a quick, extended series of Gotchas on constabulary.

Theme B explodes with Genie’s pyrotechnics of verbal tone, social verbal convention, and personally allusive verbal style.

There is almost no Sympathetic Pain humor in Aladdin.

Incongruity humor is subordinated.

After all, if we’d spent the last 10,000 years in a lamp, quite possibly watching infinite television reruns, wouldn’t we be verbally irrepressible too!

The predominance of Gotcha and Word Play makes Aladdin Advocate.

Advocate is the natural juvenile stance.

Aladdin is advocating basic terms for world peace, self-determination, and the pursuit of self-fulfillment.

Aladdin's Advocate humor personality is straightforward: somebody wins, somebody loses.

In the Reconciler film My Big Fat Greek Wedding, marriage takes a lot of painful compromise from everyone.

Reconciler personality is not a matter of standing up for oneself.

Advocate texture is likely to be self-assured, assertive, highly directed and unambiguous toward settlement.

Students suggested that humor preference could be tested for correlation with color preference.

The yellow preferences and the Consoler preferences coincided.

Blue in this scheme is superimposed on Advocate.

To the extent that military or paramilitary forces see themselves as projecting power for a stated purpose or ideal, “trying to close the deal” in favor of an espoused ideal, we would consider such forces Advocate in character.

Some military and para-military forces are dressed in blue which is a reasonable Advocate identification. Others dress in khaki which as a form of orange-brown would be identified with Reconciler.

Aladdin, the three major sympathetic characters—Jasmine, Aladdin, and Genie are all blue-clad.

Yellow is the color of pain

Green is the color of magic.

If Disney was into the coordination of all arts, we were exploring what coordination with humor might entail.

Carleton reunion attendees were asked about their long-term memory of Peter, Paul, and Mary songs.

One third, exactly, of the Carleton respondents tested as Crusaders compared with 19.8% of the control group.

Carleton athletic teams are "Knights"!

The highest correlation among the 16 possibilities, however, was a negative correlation between Advocate and “Blowin’.”

Advocate humor texture has a stridency about it.

There is a certain indeterminacy, a certain infinite regression of Crusader sentiment

Other than in sales, “razzle-dazzle” has been strongly remarked and analyzed in the prize fighting ring.

Word Play seems an ideal vehicle for constant jabbing; Gotcha provides the knockout power.

Chapter 9: Aladdin:

Do You Trust Me?

Perhaps there is no theatrical organization in all of history that has been so routinely academically ignored and minimized as the Disney organization. In fact, that’s putting it mildly. We could have said “maligned,” “distained,” “made insignificant,” or “held in contempt.” Certainly, the entire motion picture industry and in particular the American motion picture industry has been repeatedly treated with academic distain, and American universities typically have only token offerings in film, which means that all the great (that is, successful) studios get close to no academic attention.

The difference with Disney is that it has thoroughly dominated its industry, and its products are thoroughly and intimately known by college audiences before they get to college. In a certain sense, the Disney classics are the “Great Books” that unite young American culture. But neither the University of Chicago nor any of America’s other great academic institutions has suggested that critical attention must be paid to what Disney has done and is doing.

Only in the last decade has academe awakened to the fact that Disney has been a major cultural force in America. Particularly its animated films with a primary audience under puberty have for decades had a shared common mission, to influence the meaning of the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights in practical, vision-changing ways for Americans growing up. Typically, this means that Disney has had to be several decades ahead of national practice.

Consider some of these childhood initiatives in terms of later American attitudes: Song of the South dominated our sympathetic sense of Black Americans as natural family to white America; Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs broke the waves for sympathetic portrayal of physical oddity and quirkiness deriving therefrom; Cinderella and its comedic message enforced on the minds of American youth that pureness of heart and consistent humility create natural beauty and nobility, defeating all snobbish pretension of social rank. (All of these films date from the 1950’s and before). More recently Pocahontas and Aladdin have virtually defined multiculturalism and gender equality within a romantic relationship for millions of children, American and otherwise. The Disney human rights agenda, pursued now for almost 70 years, staggers any serious understanding.

1

The academic response has typically been not to undertake any serious examination. Though this neglect is not limited to Disney; it is most absurd with respect to Disney that academe refuses to grant serious consideration to the most expensive and most influential literary art form ever developed, the modern cinematic form most spectacularly influential in its American variant. For “influential,” one could easily substitute “profitable,” a fact which academe has generally been all too glad to emphasize. American film is profitable and therefore falls beneath the dignity of higher education to contemplate. Such attitudes not only destroy the ability to see the obvious in recent literature. Extended as a general principle, it makes other work—the work of Shakespeare, Swift, Pope, Scott, and Dickens, for example—bear a burden of suspicion that is considerably more than inappropriate. High literary talent wants and typically expects to get paid. Academic criticism that can’t work with that expectation can’t work with reality.

College-age students, of course, are typically embarrassed to admit ever having seen, much less having been fundamentally impressed by cartoons. They are easily led to recall anything mawkish or sentimental, anything contrived or conventional with disdain. And Disney animation as both theater and as children’s literature thus falls under easy censure. The censure, however, routinely falls away shortly after college as former collegians, as former Disney fans, return to their original loyalties in buying classics recorded on ever-increasingly sophisticated technical equipment for their own children to watch and to emulate.

Therefore, we do not apologize for bringing forth a discussion of a Disney classic as profoundly American just as My Big Fat Greek Wedding is profoundly American in its careful consideration of second-generation American challenges. Nor do we apologize for recognizing that Disney full-length animation classics are invariably comedic by the definition presented in this study and its predecessors.

Nor do we apologize for considering Aladdin, a relatively recent work, as already classic. It is a characteristic of the Disney organization that it plans its classics in advance, has every reason to believe that they will be classics, and pours money into these productions in an almost prodigal fashion, employing exclusively first-rank artistic talent in order to assure their instant classic status. Taking a non-animation example that involved Walt Disney himself acting in most characteristic ways for the Disney organization, we can cite his 20-year single-vision negotiation for rights to make Mary Poppins yet another Disney instant classic (Internet Movie Database, Mary Poppins.)

2

An entirely separate characteristic of the Disney organization, which again allows special disdain in academe, is that all its productions unite the talents of artists working in very distinct arts. This facet of Disney is most evident in animation which requires artistic specialists in cinematography and pictorial art beyond all other theatrical forms. And Fantasia, fully integrates attention to musical art and in fact carries musical imagination to higher levels than anything previously imagined. Fantasia can equally be seen as integrating dance and the most elaborate forms of choreography to the list of integrated arts in Disney classics. From an academic perspective of high specialization, all this is simply reason without end for refusing any cognitive attention to Disney products.

Academic distain aside, we turn to Aladdin which in no way deviates from the long-term Disney agendas, social or artistic. We’ve stressed Disney’s masterful integration of the arts not merely to defend Disney, but also because Aladdin can be analyzed both for its comedic import and its humor texture largely in terms of an elaborate, classical musical progression. Advanced musical forms normally have what is called A-B-A patterning, the statement of a theme, the statement of a counter theme, and a return to the original theme in variation. Both the comedic and comic structures of Aladdin have clear, simultaneous A-B-A patterning. Since choice of predominant humor is so major a determinant of the A-B-A structure itself, elucidaton of Aladdin’s comedic structure and import virtually necessitates some referencing of humor, separate from a direct humor analysis.

As Aladdin opens (at least after the “Arabian Nights” prologue of the lamp and invitation to hear its story), we are backgrounded on the nefarious dealings of Jafar as he seeks to acquire world power through possession of the lamp hidden in the Cave of Wonders. And we are simultaneously introduced to Iago, the animal side-kick who will provide so much of the comic dialog and will also make subtleties of plot entirely unsubtle and available to every member of the young audience.

Immediately after this opening fanfare of Jafar’s failure at the Cave of Wonders, we are tossed in medias res into a typical morning in the street-rat life of Aladdin. He has just stolen a loaf of bread, and now his only problem is to escape the constabulary long enough to enjoy breakfast. Here we have the first statement of the A Theme.

Aladdin’s various escapades in evading the thugs who pass for palace militia can be seen as a long progression of Gotcha jokes. Time after time, Aladdin is surrounded by overwhelming power reminiscent of the amassed police powers of The Blues Brothers. And time after time, he escapes in the most improbable of ways, ways that lend themselves to animation and preclude imitation by stunt men.

3

But having with Abu, Aladdin’s own sidekick monkey, escaped all the militia can muster against him, Aladdin settles down to breakfast in a back alley only to see urchins poorer than himself searching through garbage for something to eat. Filled more with compassion than hunger, Aladdin offers the children his bread, much to Abu’s disgust. But shamed, Abu reluctantly imitates Aladdin’s generosity.

The comedic A Theme of Aladdin then is the Street Rat Aladdin theme of living by one’s wits and one’s athleticism, depending on constant improvisation, necessarily trusting in oneself and one’s own abilities, and showing compassion to the poor even at the expense of ignoring one’s own needs and one’s own poverty. Long as this list is, any one of its components has been multiply demonstrated as successful within the first ten minutes of Aladdin. And long as the list is, each component can be reasonably argued as part of a long-term Disney interpretation of American values, not simply values as they are at the time of the movie’s premiere but as they can be shaped into the future by Disney vision of American destiny.

The comedic A Theme then is allowed a brief respite as we visit the palace, get introduced to Jasmine who is chaffing under a thoroughly un-American demand that she marry for state convenience. This minor bridging element also re- introduces Jafar as courtier and accustoms us to Iago’s comic and close-to-constant commentary.

The A Theme is resumed in variation as Princess Jasmine determines to go AWOL, escapes from the palace, and finds herself in deep trouble for her naiveté in not bringing money with her or knowing that market goods must be paid for either in cash or in extreme criminal penalties. Jasmine is saved from her naiveté by Aladdin’s and Abu’s intervention. And, modern woman that she is, she almost instantly wises up enough to play along with Aladdin’s improvisation so thoroughly that when she greets a camel with a “Good morning, Doctor” even Aladdin finds it a bit much.

With these variations, the A Theme of evading constabulary resumes in full force, the reprise yet again redundantly teaching the same survival faiths that we have already discussed. Aladdin’s comedic patterning clearly demonstrates comedic import’s dependence on redundancy. By the time Aladdin leads Jasmine safely to his strange slum roof-top abode overlooking the palace that Jasmine has just voluntarily rejected, the comedic patterning has been driven home.

4

The distant view of the Sultan’s palace allows for a thorough musical dialog of contrasting views of palace life, Aladdin seeing the palace as a pipe dream, and Jasmine seeing it as a nightmare. Along the line, Jasmine has proved herself to be Aladdin’s athletic equal, with the comment that she is a fast learner. By this point, even rather slow elementary grade students should understand that this is no place to think in terms of gender inequalities or in terms of foreign cultures. Jasmine and Aladdin may be from half way round the world and from a non-Western, exotic culture, presumably with a religion rather novel in America. But they are beautiful people in the best sense of that expression, they have both exhibited compassion for the poor (it is what has almost cost Jasmine her hands), and they both are typically American in resisting societally-imposed limitations, however much their rebellion leads in opposite directions. Again, this is already redundantly obvious in the comedy of Aladdin, and these new emphases in fact round out the A Theme.

What follows is another bridging element, supplying necessary plotting for Jafar to locate Aladdin and order his arrest, for Aladdin’s best efforts to fail against a concerted attempt to arrest him, for Jafar disguised to offer Aladdin a way out of jail and into riches by harrowing the Cave of Wonders, and for Abu’s cupidity to result in Jafar stealing the lamp, Abu restealing the lamp, and Aladdin, Abu and the magic carpet ending up disconsolately at the bottom of a now-sealed Cave of Wonders.

This bridge then introduces the second theme, the B Theme, with the entrance of Genie and the pyrotechnical verbal virtuosity of Robin Williams. The B Theme sets up a tour de force performance written in capital letters as the Genie adopts one rhetorical, literary (typically cinematic), and social stance after another to the delight more of parents accompanying their children to the theater than of the children themselves, impersonating cinematic stars, politicians, various cultural icons, and a host of others, human and non, with lightning-fast shifts of dialect and body language. Mozart, with his fondness of musical piling on, would have loved it! Plot furtherance is limited to the Genie—without Aladdin’s express wish—getting them out of the Cave of Wonders and with Aladdin’s express wish, turning him into Prince Ali Ababwa. Aladdin has also promised to use his third wish to set Genie free.

5

In terms of humor texture, Theme B replaces the repeated Gotchas of Theme A with an elaborate and extended Word Play extravaganza. And in terms of comedic import, it sets an even higher standard of altruism than concern for the poor—concern for others’ freedom. It would be hard to find a Founding Father who less adamantly believed than Disney that American freedom depends on American advocacy of freedom everywhere and that this advocacy must be a heart-issue for true Americans in every generation. (Admittedly such an assertion seems pretty serious for kid’s literature—but it is the inescapable direction of the Disney social agenda already discussed.) Theme B also portrays Aladdin, by his own wish, choosing to become something that he is not—a Prince. And as Theme B develops, so will the implications of this falsified transformation for comedic import.

Theme B continues through Ali’s, and more theatrically importantly Genie’s, triumphant entrance into Agrabah, all extended on musical lines testing just how much an audience can be made to delight in. It turns out that audiences can be made to delight in improvisational genius for a good long while.

But all good things must come to an end, and the B Theme leads into another bridge of plot elements and then back to a development of the B Theme, Ali’s attempt to woo Jasmine in a starry romantic night. Here the B Theme takes an ominous twist. While Aladdin needed the trappings of a prince in order to be introduced to Jasmine, his only hope of winning her is to tell her the truth and to live with how the truth strikes her. The Genie, having been around for a long time, instinctively has the right advice. Aladdin, the boy of the palace pipe dream has all the wrong instincts, avoids at all costs telling Jasmine the truth, comes perilously close to infuriating her beyond sufferance, and is saved only by the fact that she has, in Shakespearean fashion, fallen in love with him at first sight and is therefore willing to give him plenty of rope to indulge his life-long dependence on improvisational lies.

So the extension of B Theme material works to introduce yet another element into the comedic import, the need to be oneself for success.

It must be recognized that as Aladdin is working out this essentially American success faith based in self-discovery and self-honesty, in the B Theme Aladdin ceases to act as a comedic hero and becomes a comedic buffoon. In other words, the comedic import is enforced through a presentation of Aladdin with the heavy artistic injunction that what he is doing is not succeeding and is an opposite of any believable success formula that might be proposed. The transition from comedic hero to comedic buffoon is reinforced with a simultaneous transition from the A Theme to the B Theme.

6

The development of the B Theme of course heads again into bridge elements, the plot complication that Jafar gets control of the lamp and Genie and that Jasmine and her father are forced into abjection before a nearly all-powerful Jafar. Aladdin, having learned in the school of hard knocks and at the ends of the earth that Genie was right, flies back to Agrabah on the magic carpet determined to do or die, in the faith that Aladdin the Street Rat honestly lived is considerably upscale from Prince Ali Ababwa dishonestly endured. Along the way, Aladdin has in absentia used his second wish in order to be saved from drowning and has reneged on his promise to free Genie because he believes that without his third wish, he doesn’t have resources to survive as a prince. (By this point, the juvenile audience has made the switch over to considering Aladdin a buffoon, and the dishonesty of going back on his promise and its relationship to the overall comedic import is lost on no one.)

This then sets up the third thematic section, one in which Aladdin returns as Street Rat to confront the almost-all-powerful Jafar. This confrontation will be thematically a reprise of ideas from Theme A, including Jasmine playing along in distracting Jafar’s attention, and Abu and Aladdin playing with all the assurance of those who have nothing to lose, moving resolutely into a battle which seems hopeless only to encumber themselves with other goals like saving Jasmine from the Sands of Time. Ultimately, they win not by their pluck, not by their athleticism, and certainly not by luck, but rather by their resort to improvisational psychology. Jafar as monstrous cobra is convinced that he still is only a puny imitation of Genie’s power and is thus tricked into wishing to become a genie himself. What he doesn’t realize is that the laws of nature decree that a genie is an all-powerful being living in an eeny teeny space and subject to the direction of an arbitrary master. Jafar becomes a red genie (conveniently developed out of his original black-red-brown costume and equally conveniently contrary to the Genie blue we have become accustomed to) and is hurled back to the Cave of Wonders for an expected long residence. Gotcha humor has returned.

The third thematic section is a long Gotcha joke replacing the repetitious and close-to- instantaneous Gotcha jokes of the A Theme as originally propounded on the market streets of Agrabah.

The grand Gotcha on Jafar leads into a coda ending, the freeing of Genie and his improbably long exit, which reprises the verbal virtuosity elements of the B Theme begun in his cave impersonations. And of course Jasmine and Aladdin live happily ever after as symbolized in their moonlight ride on the magic carpet.

7

The return to A Theme elements adds little to comedic import except that we see Aladdin returned to hero status by adding to the A Theme success formula of self-reliance, generosity, quick-wittedness, and improvisation the B Theme success traits of genuineness and honesty. That acceptance culminates in Aladdin returning to his original promise and freeing the Genie, and thus activating the coda pyrotechnics. It goes without saying that respect for other people’s freedom as a moral necessity crossing all multi-cultural chasms is thus given the ultimate prominence in comedic import for Aladdin, again entirely consonant with the Disney social agenda.

It also goes without saying that college students looking back on such a movie and its somewhat syrupy comedic import may be easily embarrassed to have devoured it all so enthusiastically at a younger age. It is not so easy for the professor, who may have literally or figuratively gone to Selma in the ‘60’s, to find a good articulate argument why Disney isn’t politically correct enough to be applauded.

It further goes without saying, that we have designated as “bridge elements” almost the entire plot of the original “Arabian Nights” tale and, along with that plot, many finesses added by the Disney task force (notably almost all of Iago’s hilarious antics and dialog in Brooklynese—more advanced Word Play). The comedic import is carried almost entirely in musically orchestrated moments between real plot development. It is not a Disney invention so to do, being a consistent tendency of first-rate musicals. Aladdin is a tour de force exemplar of this high-artistry technique.

And probably not finally, it also goes without saying that the Disney social agenda by this time seems to have been designed not just for America but for the world at large. Aladdin in fact was certified in countries on six continents almost immediately.

Kid’s stuff, then, but kid’s stuff befitting a red or blue genie and obviously better if it turns out to be the work of the blue genie.

It is always a joy to analyze a Disney animated movie as an elucidation of comedic theory precisely because Disney movies designed for kids do things in undeniable and at the same time incredibly talented ways. And it is hard to deny the effectiveness of the comedic import over time as a very practical matter of political and social sensibility.

8

But what about humor texture? Is humor texture at all necessary in juvenile literature or at all understandable artistically to such audiences? And if Disney has such extensive social and artistic agendas for starters, can it possibly afford to waste time and effort on humor texture at all?

As already indicated, the humor texture of Aladdin shifts, at least strongly in emphasis, along with the A-B-A musical structure of the comedic import. The opening fanfare of Jafar and Iago out at the Cave of Wonders is only lightly comic, and that comic quality is almost entirely carried in Iago’s humorous assumption of various rhetorical stances and stereotypes.

When the fanfare ends, the scene shifts to daylight and Agrabah and a quick, extended series of Gotchas on constabulary who believe they have what it takes to apprehend Aladdin. After a plot bridge, the action returns to the day-lit market place where Aladdin, now accompanied by Jasmine continues his Gotcha triumphs.

Throughout the A Theme section, the two animals, Iago and Abu, generate humorous undercurrents with opposing verbal comic talents. Iago continually assumes verbal roles and plays them out with every nuance of New York accented overtone. Abu on the other hand is inarticulate in English, but his intonational pattern and body language make his meaning unmistakable throughout. Both are centers of near-constant humor, so constant that we come to smile continuously rather than to laugh occasionally at their outbursts.

The bridge between A Theme and B Theme is again heavily plot-centered and with the same Iago and Abu exceptions, largely without humorous drive.

Theme B then explodes with Genie’s pyrotechnics which are all pyrotechnics of verbal tone, social verbal convention, and personally allusive verbal style. Moreover, his comments are continuously being visually illustrated before us, Genie’s bee-in-the-bonnet and Mayday antics while Ali-Aladdin tries to woo Jasmine on the balcony constituting two of innumerable examples of these verbal illustrations. (Note that in the first case, “bee in the bonnet” is never explicitly stated, so the illustration stands for and speaks for the figure of speech.)

9

All of these major characteristics of the B Theme can be thought of as extremely advanced Word Play elements. They no longer fit easily into our definition of two word groups clashing with one another and move on more toward true free associational play, but ultimately they can be argued still to be clashes in the sense that parodies, exaggerations, imitations, and the like all contrast with some previously known form of utterance. Similarly Abu’s non-articulate Word Play moves toward associational free play, extending the definition of Word Play to include a humorous clash of intonations and body language.

Again, the bridge to the third thematic section, the reprise of the A Theme, is undistinguished for humor. And the reprise itself is largely formed from one huge Gotcha joke on Jafar. As Aladdin’s improvisational gymnastics have been warm-ups for the great challenge of Jafar, so the momentary Gotchas have been warm-ups for the grand Gotcha critical for success. There are, however, humorous reminiscences of the earlier B Theme Word Plays, for example Jafar asking if Aladdin is getting the point, illustrated by swords fencing him in, and Jafar referring to Aladdin and Abu toying with him as he turns Abu into a cymbal-clanging toy monkey.

In the final scene, with Jafar relegated to a lamp in the Cave of Wonders, an even more extended Gotcha that began with the start of the vendor’s tale is completed, and one final burst of Genie pyrotechnics reprises the advanced Word Play of the B Theme for an explosive finale before the closing curtain.

In short, such a review forces us to accept as lead humor elements of Aladdin Gotcha, both in short and extended forms, and Word Play in very advanced forms that the Disney organization has perfected over decades as an art unto itself.

We have not made this determination by employing the normal constraints of quadrilateral step-by-step analysis. Suffice it to say that there is almost no Sympathetic Pain humor in Aladdin except perhaps for Abu’s plight when he is turned into an elephant. The joke of a monkey-turned-elephant trying to peel a banana goes by so swiftly that it may hardly be intelligible, and it is less intelligible because it is a kind of humor that we aren’t expecting.

Similarly Incongruity humor is subordinated, though the monkey-as-elephant joke would qualify for Incongruity as well. At first, it may strike many audiences that Genie’s impersonations of cinematic celebrity styles is Incongruous. But they pile one on top of the other so swiftly that they lose their force as Incongruities and become instead simply consistent quirks of Genie mentality, consistent within his whole life ambience and irrepressible creativity. (And after all, if we’d spent the last 10,000 years in a lamp, quite possibly watching infinite television reruns, wouldn’t we want to be verbally irrepressible too!)

10

The Sultan’s inanity provides some small Incongruity pattern, but it is mainly swallowed up in the consistent American juvenile literature pattern of treating authority figures, starting with parents, with mild contempt (and thus fundamentally the butts of Gotcha humor.) Audiences over 30 can only hope that juvenile audiences are not too profoundly influenced by this Gotcha pattern.

So the argument for Incongruity as a lead element has some sense to it, whereas Sympathetic Pain has virtually no argument at all as a lead humor type. The predominance of Gotcha and Word Play (in advanced forms) makes Aladdin Advocate (probably of a very advanced form). Any argument attempting to assert that Incongruity is a lead element has to decide whether to replace Gotcha or Word Play. That decision is the ultimate argument against the consideration of Incongruity in the first place.

Arguments for the appropriateness of an Advocate humor texture are easy to come by and various. We consider the range of theoretical arguments briefly below, reserving admittedly very odd empirical evidence for its own sub-section.

A first theoretical line of argument is that juvenile literature is comfortable with Advocate texture because Advocate is the natural juvenile stance. It is important in this regard to notice that the typical baby is an advocate within moments of being born, doctors having long ago noted that infants’ advocatorial stance can be manipulated by a spank on the butt to produce a loud cry of complaint and demand which serves the additional function of getting air into the baby’s lungs.

A second, analytically-based, theoretical line of argument is that both Word Play and Gotcha humor are appreciated in early childhood development. The “Knock, Knock” jokes of the third-grade playground typically already demonstrate some proficiency in both Word Play and Gotcha, often incorporated into the same joke. Incongruity humor takes a steady knowledge of what things go together and what things don’t. Such confident knowledge takes years to acquire and anything but the grossest forms of Incongruity humor seem to await later development. Sympathetic Pain is such an advanced form of humor that most people have not ever clearly differentiated it from Gotcha or other pain humors, though the common distinction between “laughing at” and “laughing with” someone shows at least some awareness in most adults.

At a much more literary level, Advocate texture for Aladdin accommodates itself easily to the Disney social and artistic agendas. Aladdin is advocating basic terms for world peace, self-determination, and the pursuit of self-fulfillment. It is not surprising if that advocacy shows in humor texture.

11

We noted earlier that humor test respondents often have trouble distinguishing conceptually between Advocate and Reconciler humor personalities. Our consideration of the Advocate comedic import and texture in Aladdin now can help us elucidate the difference between these two humor personalities. Recognizing that both Aladdin and its humor opposite, My Big Fat Greek Wedding, define and symbolize comedic success with a marriage, a marriage of two people from very different cultural backgrounds, we can ask ourselves in each case what does it take to make that marriage happen. In the case of Aladdin, it takes Aladdin’s strongly asserting—advocating—his own strengths and self-identity, it takes Jasmine advocating a new way of doing sultanic business to her father, and it takes the villain Jafar getting got. It is straightforward: somebody wins, somebody loses, the Sultan losing happily while Jafar is considerably more discomfited. But the couple lives proverbially happily ever after. The deal is sealed.

In the case of the Reconciler film My Big Fat Greek Wedding, marriage takes a lot of painful compromise from everyone, most notably from Ian and Toula. It takes Ian accepting oily baptism in the Greek Orthodox Church, it takes Toula acting as wave-breaker and mediator, and it takes everyone letting go a little of what each has been. Everybody is somewhat discomfited in order than no one be banished to a Cave of Wonders. Does the couple live happily ever after? My Big Fat Wedding is not children’s literature. The more adult humor of Incongruity and Sympathetic Pain, as well as plot elements such as the continuation of the tradition of Greek school into the next generation, convinces us that future happiness is dependent on continuing compromise and reconciliation. Most of all, Reconciler personality is not a matter of standing up for oneself but rather of throwing oneself into a difficult and painful situation in order to make the best of it, typically by becoming quite a different person oneself.

Generalizing quickly from these observations, Advocate texture is likely to be self-assured, assertive, highly directed and unambiguous. Perhaps most of all, it moves toward settlement, toward a sealed or done deal, and in this sense, Advocate texture moves toward finality and closure.

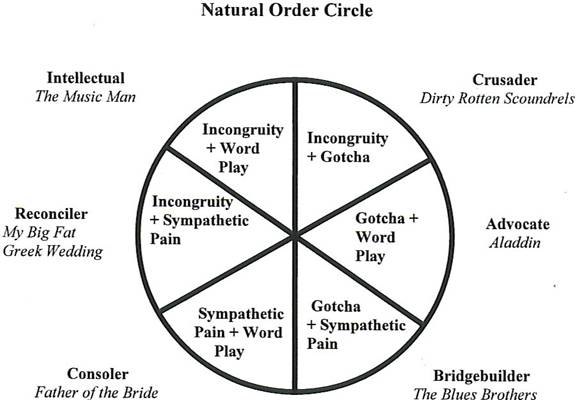

The Advocate humor texture can be even more sharply elucidated with the results of empirical research. But before delving into such intricacies, we should pause to note that with the designation of Aladdin, we have now completed our circle of literary humor personalities of the mind, with each of the six personalities associated with a different film as illustrated in Figure 4 below:

12

Figure 4

As we turn to empirical corresondances with humor preference, it will be helpful to keep this schematic in mind.

13

◄►◄ Empirical Correspondances with Humor Preference ►◄►

Moving from literary critical argument to empirical research, certain very odd results have surprising relevance to Aladdin as Advocate humor texture. The oddity of these results has been anticipated in previous literary criticism and even draws a name from 19th Century French literary thought, the name “correspondance.” While we were aware of the “correspondance” literary tradition,” its relevance to our empirical humor investigations was somewhat accidentally discovered. In the first years of the Winona State testing program, students in literary criticism sections were routinely asked to consider the possibility of empirical demonstration within the field of literary criticism, which has been non-empirical virtually throughout history. The Humor Quotient Test was used to make such discussion possible and intelligible, and eventually students were asked what kinds of experiments they could think of that might throw light on literary theory.

In one of these sections it was suggested that humor preference could be tested for correlation with color preference. HQT respondents that term therefore took the HQT and a side test asking for color preference. Respondents could respond with any shade, but answers were simplified to a color spectrum of blue, green, yellow, orange (including browns), red, and purple.

The results were close to unbelievable. If the color wheel was superimposed on the Natural Order Circle with Red superimposed on Intellectual, purple superimposed on Crusader, and so forth around the color wheel, a strong coincidence between color preference and humor preference appeared. The most notable result was that out of 30 respondents, two chose yellow as their favorite color. Two HQT respondents tested Consoler. The yellow preferences and the Consoler preferences coincided.

This was, again, a student initiative, and we have not pressed the color preference correlation in our later studies. But it is interesting to note that blue in this scheme is superimposed on Advocate. Arguably advocatorial forces like U. N. Peacekeepers and most American police forces are dressed in blue.

At this point, we can hear the objection: “Wait a minute, don’t I remember your saying earlier that Reconciler, not Advocate, is the army code and can also be aptly thought of with respect to firefighters and police? Yet here you are arguing a correspondance between Advocate-blue-and police? Aren’t you contradicting yourselves?”

14

The point is well taken. But it must be remembered that we have also argued that while Intellectual and Bridgebuilder are clear cognitive opposites for most people, Advocate and Reconciler are easily confused and commingled.

To the extent that military and paramilitary forces like police see themselves as throwing themselves into conflict, they probably see themselves under something of an army code which is easy to understand in terms of our Reconciler definition. Firefighters rushing into the burning World Trade Center are a noble picture of that Reconciler instinct.

To the extent that military or paramilitary forces see themselves as projecting power for a stated purpose or ideal, “trying to close the deal” in favor of an espoused ideal, we would consider such forces Advocate in character. U. N. Peacekeepers, by their very name, seem to epitomize that advocacy of peace. Police on regular patrol in a basically law-abiding city are similarly visual advocates for keeping the city that way—law-abiding. And as of the fall of 2008, the U.S. Army military began an initiative to train Army units home from overseas deployment to provide assistance here in the U.S. in the event of terrorist attacks or natural disasters, presumably law-and-order advocacy work.. Simply reviewing the number of words here taken to separate out the Reconciler from the Advocate role is one of the strong proofs that the various axes of the Natural Order Circle are not of equal length and that the Reconciler-Advocate axis is often too short for the poles to be clearly distinguished without very careful thought.

So, without apology, some military and para-military forces are dressed in blue which is a reasonable Advocate identification. Others dress in khaki which as a form of orange-brown would be identified with Reconciler.

Additionally in support of an Advocate-blue identification, in Catholic theology, the Virgin Mary is called ‘mediatrix” (“mediator’) and in Catholic iconography she is dressed in a sky blue mantle. “Blue laws” may make people blue, but they also advocate a stern morality. “True blue” people are loyal to an ideal and presumably consistent advocates thereof. “Blue-blooded” has often been analyzed as referring to paleness from an upper-class aversion to tanning. Perhaps it also refers to those who are the pillars and advocates of monarchical society.

Turning more directly to Aladdin, the three major sympathetic characters—Jasmine, Aladdin, and Genie are all blue-clad, though in different shades. If the reader is willing to accept the original empirical correlation of color to humor preference, then there would seem to be a quite unusual harmony established in Aladdin between sympathetic character color identification and overall humor texture.

15

Not every movie shows heavy color coordination of costume—though there are some well-known color conventions of costume in juvenile literature, as for example black reserved for villains in Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, The Wizard of Oz and Aladdin’s own Jafar. (White, the Sultan’s color in Aladdin, has some conventional association with vacuousness.)

Musicals are more likely than regular drama to display highly patterned artistic coordination of all types, so we might consider the red coordination of Music Man for a moment here. In Christianity, a red flame iconographically is the sign of the Spirit. In the secular Western tradition, this is often transmuted to be the flame of intellect. And of course we have labeled The Music Man Intellectual and highlighted its mental and visionary qualities from the “Think System” to the visionary final march in broad daylight and resplendent red uniform.

It might even be worth consideration of non-musicals. In My Big Fat Greek Wedding, our abiding first impressions of Toula as frump originate from restaurant scenes in which she is dressed in non-descript and baggy earth tones. In our simplified color scheme, these muted shades would all have been grouped with orange and brown, which experimentally are colors superimposed on Reconciler in the Natural Order Circle.

No doubt color coordination artistically often has nothing to do with humor and for very good reasons. In Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, the color scheme seems to center on the blue of the sky and ocean combined with fundamentally white buildings and even white suits for the men. This color coordination has nothing to do with the purple which would be anticipated for Crusader humor texture but has everything to do with the local color realities of the Mediterranean and, perhaps more distantly with French upper class realities (note the absence of red from the Tricolor scheme).

So while we have never pressed forward empirical studies of color coordination with humor, we do note it in passing, and it often seems to make a great deal of sense. (We were once in discussion with an art therapist and mentioned these color correspondences. She jerked with shocked surprise when we got to yellow as the Consoler color. Recovering, she pointed out that in art therapy yellow is the color of pain and that art therapists look for a decrease in the use of yellow in patient artwork as diagnostic of recovery from traumatic illness.)

16

Additionally the color coordination experiment did suggest to us as researchers that there might be uncharted depths of relationship between humor and other parts of our human experience. We knew that literature was full of symbolic uses of color, as for example green is rather consistently, among other things, the color of magic, from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight on. That too made sense in our color experiment; magic is the bridge to dimensions other than those of our common-sense world, and green would be superimposed on Bridgebuilder in the Natural Order Circle

These strange relationships are not so strange in literary criticism. French 19th century romantically-derived criticism, originating with Baudelaire’s Fleurs de Mal in 1857, had made quite a point of “correspondances” between similarly unrelated classes of ideas. And in the 20th century Canadian critic Northrop Frye made a quite deserved international reputation for his Anatomy of Criticism and its encyclopedic cross-referencing of conventional sets of disparate ideas (and incidentally grouping these sets under six different phases of literary experience.). And thus the color preference experiment became the progenitor of other experiments exploring the link between humor and seemingly unrelated sets of human experience. If Disney was into the coordination of all arts, we were exploring what coordination with humor might entail.

And in fact continued research correlations between humor and other aspects of human experience has given us further clues as to the nature of Gotcha plus Word Play, which we gave the tentative rubric “Advocate.” It must be recognized that establishing any empirical results for humor, much less “correspondance” results has been entirely dependent on finding volunteer respondents. We have been extraordinarily blessed by the number of people who have voluntarily come forward to help—and very often we mean precisely that—they offered; we didn’t ask.

It was that way when Paul volunteered to be part of the reunion committee for his 45th Carleton College reunion. Carleton, according to U.S. News and World Report ranks first in the United States among colleges and universities in its percentage of alumni giving, and that by a very wide margin. The Carleton Voice, the alumni magazine, once a year devotes its main coverage to reunion, and as Robin says, each year the pictures of alumni classes get more and more distant and the names beneath get smaller and smaller in order to fit everybody in. So Carleton reunions are unique occurrences, and one of the extraordinary things about these three-day affairs is the variety of alumni speakers who make presentations on where life has led them.

17

Somewhere along the line, Paul mentioned that we were humor scholars, and almost immediately it was suggested that Paul (’66) and Robin (’69) make a humor presentation at reunion, administering the Humor Quotient Test. Since we administer the HQT for research purposes, not entertainment, we began thinking what kind of side test would be elucidating with such a group. We eventually decided to test whether humor preference could possibly have anything to do with Class of ’66 long-term memory of Peter, Paul, and Mary songs. Peter, Paul, and Mary had appeared at Carleton during the Class of ’66’s sophomore year, and their albums had played across campus for the next several years. But 45 years later, would anyone remember, much less respond in ways linked to their later-life humor preferences?

About 80 alums showed up for the presentation, better than half of them from later classes. And surprising to us, everyone wanted a shot at the folk-song side test, even people from the Classes of ’91, ’96, and ’01. We always let people do what they want when they have been so kind to volunteer, but afterward we did sort out the Class of ’66 for the side test analysis.

Even before separating the Class of ’66 and getting to the side test, there were interesting results. For this test, we compared databases of largely college-educated adults over 30 (n=106) to 63 usable Carleton responses. One third, exactly, of the Carleton respondents tested as Crusaders compared with 19.8% of the control group. There is less than a 1% chance of such a result happening by accident rather than representing a real bent. Similarly impressive was the result that only 4.8 % of the Carls were Consolers compared to 13.2% of the control group. These results, indicating a strong bent of Carleton grads towards Crusader humor, are impressive in themselves, but more impressive when it is recognized that Carleton athletic teams are “Knights”!

The side test highlighted four Peter, Paul, and Mary Songs: “500 Miles” “If I had a Hammer,” “Stewball,” and “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Respondents were given five questions, in each of which respondents allotted ten value points among the four songs by a specified criteria. The sum of a song’s points over five questions was taken as the value the respondent placed on that song.

18

The Carleton ‘66 audience gave the highest combined value points (by a wide margin) to “Blowin’ in the Wind” (remember, it was the Flower-Child Era). And not surprisingly, there was a very strong correlation between Crusader score and preference for “Blowin’in the Wind.” The highest correlation among the 16 possibilities, however, was a negative correlation between Advocate and “Blowin’.” And the highest positive correlation for Advocate, the fourth highest correlation recorded, was with “If I Had a Hammer.” For anyone who doesn’t remember the song, it continues, “If I had a hammer . . . I’d hammer out justice. . .” (Seeger). That sounded pretty Advocatorial to us.

Extrapolating from these results, we’d suggest that Advocate humor texture has a stridency about it. And with that stridency, it has a strong tendency for a final verdict and a clear-cut conclusion—in Aladdin that seems fulfilled in Jafar’s one-way trip to the Cave of Wonders.

And this strident win-lose feel contrasts with Crusader, even if Crusader is right next door on the Natural Order Circle. If “Blowin’ in the Wind” is emblematic of Crusader (“How many roads must a man walk down before they can call him a man? … The answer … is blowin’ in the wind.”) (Dylan), then there is a certain indeterminacy, a certain infinite regression of Crusader sentiment that is something of a natural opposite of the clean, clear-cut, win-lose Advocate mentality. (Think back to Dirty Rotten Scoundrels: one con always leads to another, one contest for supremacy in the con world only leads to a higher competition.)

Advocate, of course, in many European languages is a high-tone word for “lawyer.” There are other Advocate professions, sales most notably. These are all characterized by their clear-cut, win-the-case, make-the-sale, close-the-deal objectives. In their highest proponents, they are also often associated with a “razzle-dazzle” feeling. Harold Hill is a razzle-dazzle salesman in his harangue on River City’s trouble: “With a capital ‘T’And that rhymes with ‘P’ And that stands for Pool”—and we have already recognized some relationship between Music Man and Advocate texture.

Other than in sales, “razzle-dazzle” has been strongly remarked and analyzed in the prize fighting ring, particularly in its highest proponents like Mohammed Ali. A razzle-dazzle style of boxing is likely to combine fancy footwork with devastating punches, or to combine incessant jabs with perfectly timed devastating blows with the dominant hand previously held in reserve.

All of these seem relevant to Advocate and to Aladdin in particular—consider the fancy footwork of Genie throughout the B Theme and in fact throughout the film. From an analytic side, Word Play seems an ideal vehicle for constant jabbing; Gotcha provides the knockout power.

So we’d submit, starting not from literary criticism but from empirical investigation, that the feel of Advocate texture is a strident, clear win-lose texture which in its highest achievements will probably feel very much like the work of a superlatively talented, razzle-dazzle boxer. And in the work of Robin Williams as Genie, we know of no more superlatively razzle-dazzle, verbal virtuoso performance.

19